|

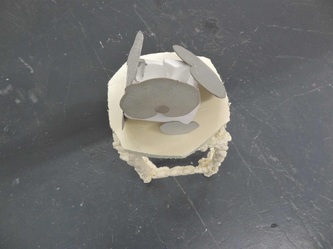

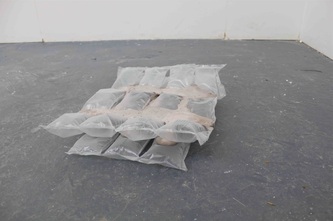

The private view for my group show at Studio 1.1 was exciting, not least because someone managed to knock down one of my two pieces on display. It didn't break badly, so I suppose the ratio 'annoyance / experience value' was ok in the end. This is the piece, on the right of the image, prior to the incident. It's called Wedge pour. I also showed this one, called Air Grid Pour. My best work ever, though, didn't make it to the show. It arrived on the 15th of January. You can still see the show until Sunday 27th January. Actually, there will be an end-of-show afternoon on that Sunday, from 4 to 6 pm. We may come round with my masterpiece.

0 Comments

It's been a while since my last post from Nepal. Heathrow, four days of culture shock and straight into my masters. I'm really enjoying it there. Great chats with fellow artists, good tutorials, hearty lectures. (The current exhibition celebrating 175 years of RCA is called 'The Perfect Place To Grow'.) I've been busy playing with concrete, foam and bubble wrap, and thinking about herding matter, enclosures, structures made out of formless materials and how our bodies negotiate the city. I also tried a bigger piece for my end-of-term crit. Concrete and polystyrene, approximately 140 x 190 x 70 cm. My next piece of work, my best one ever, will arrive sometime very soon. I don't expect to have much time for anything, but I'll try to add something about my next group show at Studio 1.1. PV on January 3rd, 6-9 pm, 57a Redchurch St, London E2 7DJ.

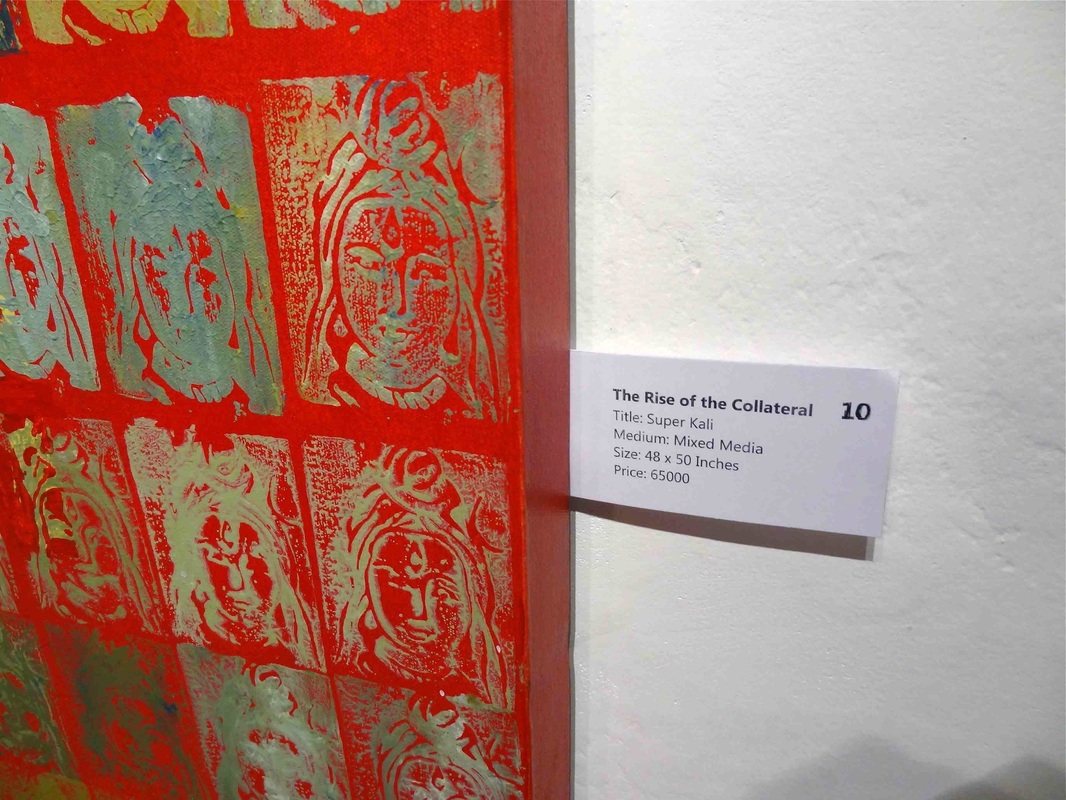

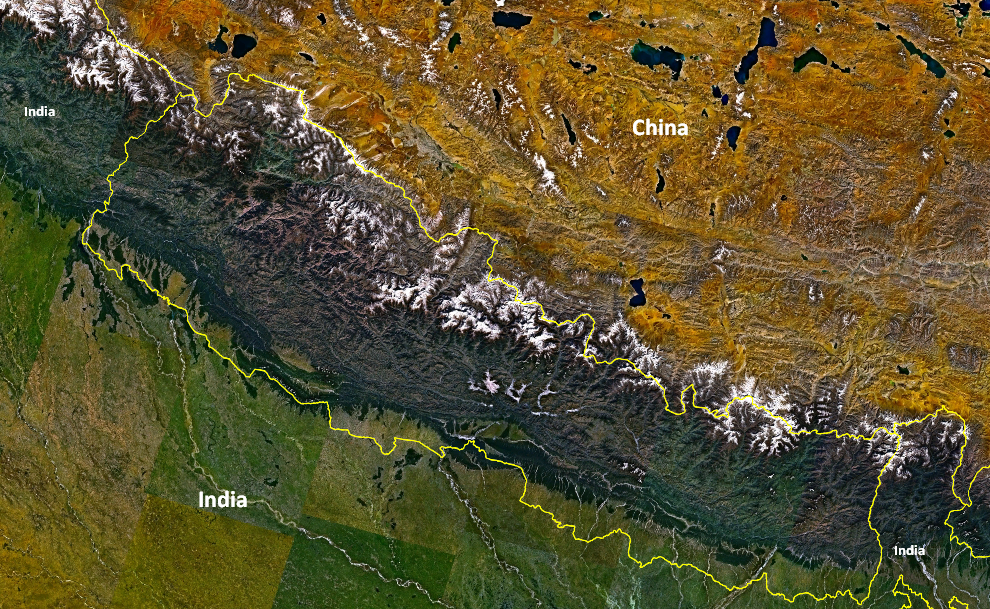

I've been waiting for a while to write this last post about Nepal. I wanted to absorb as much as possible about the contemporary art scene, just to give my views a fair chance of fight against my ignorance. What I didn't know was that, in the last of my ten months here, an incident would bring the whole matter poignantly into focus. On the 11th of September, members of the World Hindu Federation stormed Siddhartha Art Gallery, the main contemporary art gallery in Nepal. Their target was the young painter Manish Harijan's show 'The Rise of the Collateral'. In his works, made during his KCAC residency, the Hindu and Buddhist pantheons meet the world of Western superheroes. Bhairav play-fights with Captain America and Ghost Rider hangs out with Buddha. The image that seemed to attract most of the wrath of the religious extremists was Super Kali, a representation of the goddess Kali (the violent goddess of time and change) giving the finger in a miniskirt. The artist received death threats from the aforementioned right-wing Hindu fundamentalists, the police closed down the gallery and both artist and gallery owner Sangita Thapa (also co-founder of KCAC) were requested to give evidence at the District Administration Office in a Kafkian victim-perpetrator role reversal. In the end, a line was drawn between artist and gallery: the authorities recognised the gallery's right to protection against the threats of violence but not the artist's. The office of the UNESCO in Kathmandu issued a statement defending the artist's right to expression and part of the local art community organised protests and debates about the incident. I write 'part' because most senior artists, according to the young artists I spoke to, decided to keep quiet. The gallery was reopened after the owner promised not to repeat this kind of exhibition in the future - thus effectively admitting culpability. In contrast, the artist is still in hiding and is considering leaving the country. This story made me think about many of the issues that hinder contemporary Nepali art. Politics, politics everywhere One of the first things you notice in the Nepali art scene is how mediated by politics (party politics, ethnic/caste politics and gender politics) it is. Access to the scarce resources destined to the arts in this country may be greatly dependent on which political party you have connections to and what your surname/ethnic background/caste/gender is. Isolation Nepal is a landlocked country wedged between the two Asian giants, India and China. It has long been isolated from the wider world due to its geography, its poverty and the role of the ruling classes. Art hasn't escaped unscathed from this. Nepali artists tell you that 'modern art' -as opposed to traditional art- started here in the 1950s, after some ideas overheard in Europe arrived in Nepal. You can still see them staggering around like zombies in the work of older artists, alongside long-standing subjects like the Nepali landscape, traditions of different ethnic groups and references to religious and architectonic icons (gods, pagodas, stupas and the like). Contemporary art, in the sense of an art that asks questions about our time, is a newcomer, but it has been enthusiastically embraced by a new generation of artists under 30, who cast their net wide over subjects that affect their lives in the present tense. Amongst them, the clash between traditional and Western values and concepts features prominently. So the spirit of the paintings which those Hindu extremists wanted to burn was hardly new. Still, Manish has become the first artist victim of religious extremism in (comparatively) moderate Nepal since the end of the ruling monarchy in 2006. As this article explains, behind the incident there are political motivations, which come thickly mixed with religion, caste and nationalism. Secularism, although nominally present in the current post-conflict interim constitution, remains a myth, according to this other article. Generational divide. Support for the threatened artist came from young artists and very few older ones, mostly tutors from art schools. In their view, the 'senior artists' (many of which have found ways of securing salaries, funds and privileges by playing the political game) saw this as an opportunity to strengthen their position. Consulted about the incident, some of the 'seniors' reportedly said that young artists deserve this kind of response, as they have dared to change the ways gods and traditional motifs are represented in ways that their elders have never attempted. To top it all off, the minister of culture (from the surreally conglomerated Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation) didn't say a word in defence of freedom of artistic expression. Who needs contemporary art? Contemporary art is predominantly ignored in Nepal. As Manish L. Shrestha (one of the very few Nepali artists who show abroad) said in a recent discussion, contemporary art in Nepal has failed to reach the general population. And it is true that you keep seeing the same faces in every one of the limited art openings in Kathmandu - mostly artists' faces. But there also seems to be very little interest and understanding from the Government and the general public about contemporary art and the role that it can play. In a country trying to find its identity after years of paternalistic monarchy, exclusionary caste politics, isolation, conflict and ongoing influence from powerful neighbours, contemporary art becomes a necessity, one of the few activities that can offer the nation both a mirror in which to understand itself and a laboratory to imagine its future. Contemporary art centres are all but non-existent in Nepal. The art market is not big or mature enough to leave the promotion of the arts to private initiative alone. And the weight of traditional art, mostly religious in subject, ensures that funding falls on its side of the scales. Most Nepalis cannot name a single contemporary artist and, if they happen to see one of their works, they are likely to wonder why they'd want to make 'those modern paintings' instead of a beautiful thangka. It's not surprising then that, when the police turned themselves into art judges to assess Manish's work, their verdict was that the artist should paint beautiful paintings that conform to the traditional ways and refrain from interpreting gods. Incidentally, I had a chat with a traditional sculptor in Patan, the home place for traditional metal sculpture, and he told me about his surprise with the whole polemic, since all through history people in his trade have regularly changed, merged and adapted the depictions of gods. But the idea of historical change has been hijacked by party politics. In the current political tension, change has come to be associated with the ruling coalition of Maoists and ethnic minorities, who are rubbing aggressively against the former status quo. The reaction to change from this status quo is seeping out into economy, tourism and -as we've seen in this incident- art. 'Is there a Nepali contemporary art?' Traditional art from Nepal is well represented in museums and collections all over the world, particularly metal sculptures of gods made between the 6th and the 15th century. But when a Nepali contemporary artist introduces itself as such abroad, the question often comes back: 'Ah, but... is there a contemporary art in Nepal?' Some of the international artists I've met in Kathmandu seem to arrive attracted by a nostalgic and anachronistic view of Nepal as an ancient haven of temples and venerable traditions. This post-colonial 'noble savage' hangover doesn't help the local art community, who are trying to deal with a situation in which social inequality and corruption are as real as the pagodas of Durbar Square. Even more worryingly, the work of these visiting international artists tends to offer little inspiration to young artists trying to navigate contemporary art practices. Ke garne? What to do? Many of the things that could help contemporary art in Nepal are already in the hands of time. As the older generation retires, there will be a chance for the artists that are now young to apply a new kind of thinking. In any case, I will venture into the dubious business of giving advice, some of which I've already offered to some artist friends after a few drinks. Invite great artists to come Write personally to artists you admire. Ask them to come and give a talk or do a project with you. You never know. They may just be waiting for an invitation like yours to take a break. And they have the contacts to find the necessary funding. Bring some foreign curators Nepali artists need to show abroad. Go to the foreign embassies in Kathmandu and ask for a small grant to bring here a curator from their own country (for example, Germany or Denmark). Sell it to them as an affordable key project of post-conflict identity-building through art (which is exactly what it is). The curator gets a free holiday, meets a whole new art scene and maybe one day includes some of you in one of his shows. Go online No, really. The amount of resources available to keep up with new developments in contemporary art is never-ending. Try: http://www.e-flux.com/ http://www.thisistomorrow.info http://artforum.com/ http://www.arte-sur.org/ http://artsy.net http://www.frieze.com/magazine/ And that's all from Nepal. Now it's RCA time. Mekh, Sanjeev, Bikash and everyone else: Good luck, thanks for those open arms and see you again, some happy day.

With the residency show behind me, it's time to catch up on smaller to-do items. For example, I have this bunch of photos I've been collecting under the slightly pompous title 'Visibility of the process'. Like I mentioned in an early Nepali post, a normal pedestrian here has visual access to the innards of building works in a way that has become rare in developed countries. Think of Britain, with its panoply of hoarding arrangements to keep building sites concealed, and which are only taken down when the work is complete, as if to ensure that your first view of the 'product' is that of a finished, sealed, impenetrable entity. Here you can read things more easily, take them apart in your mind, retrace the steps of their making. There is also more mending and making do, and more acceptance of it in the public and professional spheres. The boundaries between the domestic, the private, the professional and the public are permeable, if at all present. Workshops are open to the street, squares double as factory yards. All sorts of activities happen in plain view, including very graphic religious practices. Meanwhile, back in the West, we try to reconnect with the making of things through sheep-shearing demonstrations in country fairs and knitting sessions for the trendy in some reclaimed Working Men's Club, while all sorts of post-apocalyptic movies and zombie series pose the question: If everything went tits-up, what skills you got?

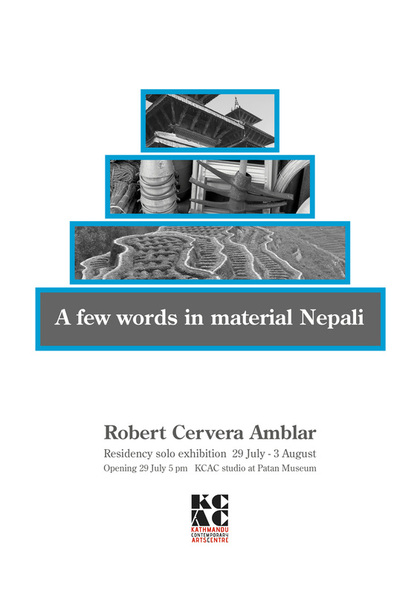

On Sunday 29th July, my exhibition poster took its place at the entrance of Patan Museum. Cut to KCAC studio, around 4 pm: And a bit after 5 pm: It was a great evening. People seemed to enjoy the work and I had good conversations, particularly with Nepali artists and art students. For many of them, the work showed an openness towards materials, subject and presentation that they found new and encouraging. And then, a few glasses of chhaang later, my first solo show opening was over. Yesterday (two days before the general opening) I held a private view for the staff of Patan Museum. Loads of tea and biscuits and a small speech to encourage them to go in and look around with a sense of entitlement. Apart from finishing a couple of pieces for the show, these days I'm mostly doing gallery admin: posters, handouts, lists of works. For instance, this is the A4 handout I will make available during the exhibition: My end-of-residency exhibition officially opens in eighteen days. That's Sunday 29 July. Here's the poster I've designed: I've decided to do a pre-opening on the 27th only for the museum staff, who have been nosing around, talking between them and wondering what the hell that white guy is doing since I started working here. I don't want them to be put off by all the people in the main opening. I want them to come in and properly, openly nose around.

Talking of nosing around, here's your (virtual) chance, before everything is set up for the show: One of the interesting things about this residency in Kathmandu is that you get to share your space with a local artist. I'm sharing the studio with Mekh Limbu, a skilled painter and impromptu tree-climber. We talk art, we look longingly at the occasional bout of rain (the monsoon has started) and we take it in turns to play music. He plays Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and sometimes music from his ethnic group, the Limbu (as it often happens in Nepal, the name of his ethnicity is also his surname). I play Joan Manuel Serrat (a Catalan singer-songwriter) and loads of flamenco, which he likes (check out Enrique Morente's take on Leonard Cohen).

You can see Mekh's work on http://tumsamekh.wordpress.com/work/ |

Robert Cervera Amblar

Sculpture, installation, writing. Archive:

July 2013

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed