|

Over the last few months I've been photographing examples of containment in Kathmandu, as a general category of everyday material actions and contraptions. Coincidentally, I've just returned from London, where I saw two very different kinds of show that, in one way or another dealt with this notion. The first one was Richard Deacon's new show at Lisson Gallery. As is the case with some of his sculptures, the idea of a central void, bound and made present by the body of the piece, could be felt in Congregate, a stainless steel work shown in the courtyard: On a very different note, Damien Hirst's retrospective at Tate Modern reminds us what a good patron of the guild of vitrine makers he is. Here, his work doesn't attempt to contain and give entity to the void à la Deacon, rather it is the work's vacuousness that seems to be in need of containment in order for it not to dissipate entirely. Be that as it may, here are some Nepali examples of containment and enclosure.

0 Comments

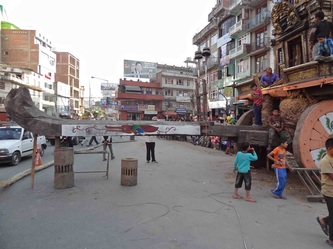

Had you walked into my studio two weeks ago, you would have seen this: And if you popped in today, it would look more like this: This is easily going to be my largest post so far, but maybe the image below will justify it for you as much as it did for me. This wooden chariot is Rato (Red) Machhendranath's temple chariot. Machhendranath is the Nepali Hindu god that protects the Kathmandu Valley and controls the rains and the monsoon. The people of Patan, who often mix Hindu and Buddhist beliefs without batting an eyelid, also consider him an incarnation of Avalokiteshvara, the Buddha of compassion. The crucial part is Machhendranath's control over the rains. If you want a good crop, you have to build him a towering temple chariot and pull it by hand through the streets of Patan. (As I write this, it's already pouring down. Result.) I had heard stories about how much taller the chariot used to be and how people had been crushed to death by its fall. Nowadays, the height is capped to avoid accidents, but the chariot and its construction still kept me geekily hooked, following the progress and asking too many questions. The smiley man in the blue cap below, Rameswar, not only answered them all, but also invited us to have dinner with his family to celebrate the completion of the chariot. Thanks again, Rameswar. The chariot is made of wood, bamboo (used as ropes to tie up and cover the structure), steel (wheel axes) and natural fiber ropes. The majority of hard parts get replaced every twelve years, some every six. The structure starts going up, following a plan fine-tuned through generations. The chariot makers are all volunteers and their knowledge is handed down from father to son. Bamboo strips are brutally and beautifully woven around the wooden structure. Next, the wheels go in. And then the ropes to control the tilt of the whole tower. More trunks are added to cover the basic structure, and the wheels and the main platform are painted in a reddish orange. A few miles of bamboo strips and a gilded temple fascia complete the coverage of the structure. And in case you needed more visual kudos, here's a huge trunk in the shape of a giant ski to front the chariot. The final touches are added while the crowd gathers to celebrate the end of the construction process. The chariot is used in the same location as a temporary temple for a couple of days. And then it's time to move it - or at least try. E la nave va. Day by day, sneaking around the city streets. The procession can take weeks, but there's no hurry. Every night, wherever the chariot stops, a holy place springs up. Sculpture, performance, social/relational art, faith and rain. Materiality and spirituality still getting on. To buy sheet metal and long rods, you go to a hardware yard and hop your way through characterfully unstable piles of metal. You find a delivery guy, let him strap everything onto his pick-up bike and then sit on top, ready to be pedaled to your studio together with your shopping. To buy clay, you go to a town full of potters (like Bhaktapur) and ask one of them to divert some of his stash to your rucksack. To buy plywood, you repeat the circus act explained above. For smaller stuff, you get yourself a bike. |

Robert Cervera Amblar

Sculpture, installation, writing. Archive:

July 2013

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed