|

Marrigje has been my fellow artist-in-residence in Kathmandu for a few months. She's now back home in the Netherlands and I will miss our chats and her insightful comments. Before going, though, she gave a talk at a local art school: During the last ten years, she's traveled through China, Laos, Thailand and Mongolia photographing interiors whose inhabitants are felt but rarely seen. In her monastery kitchens (the place between everyday life and religious life, as she put it), the pots, the hobs, the smoked walls, all speak of daily routines and the people who perform them and, in turn, are shaped by them. (She's also photographed Louise Bourgeois's kitchen and Brancusi's atelier. I wonder how those shaped them.) She came to Nepal with a new pinhole camera, a beautiful wooden box whose outcomes are as unpredictable as potentially rewarding. Exposure times vary between ten minutes and two hours. As she explained, that changes the rules of the game. There is no 'decisive moment'. Photography becomes a time-based medium, a literal layering of moments. Other technical peculiarities of her pinhole camera bring the results closer to human vision. There is no depth of field, everything is softly in focus at once. Since there is no lens, there are no perspective distortions. And it registers exactly what our eyes see without the interference of the brain, which by default does things like straightening the image. On the other hand, the longer exposure produces a colour shift, as the layers in the negative are allowed some chemical party time. A final bonus about her new camera is that local people think it's some kind of toy. Take out of your bag a Hasselblad, set it up and you've already changed the feeling of the place. Take out a wooden lensless camera and people will keep business as usual, if anything amused by this European lady and her funny wooden box.

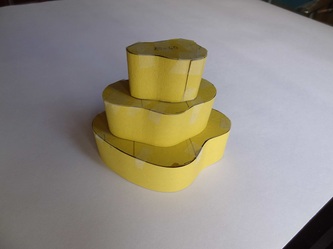

You can see more of Marrigje's photos at http://www.takeadreamforawalk.com/ Here's a new sculpture, made together with a family of steel furniture makers in Patan. I'll probably call it Gara, a Nepali word for a terraced field. Alexis Jakubowicz (b. 1986 in Lyon) is a French art critic who has been a regular contributor to Libération and Art Press since 2009. He also happened to visit Nepal last month as the final stage in his 7-month trip around South America and South East Asia. He came to see me at my residency studio and we chatted about his trip, my work, what Nepali art is up to and Miquel Barceló. (He recently interviewed Barceló and saw a parallel with my work and my interest in materiality. Needless to say, I rather liked Alexis.) He also gave a talk at Siddhartha Art Gallery titled '200 days away from home: being an art critic in a global village'. After meeting artists, curators and dealers in 11 countries (Perú, Bolivia, Chile, Cambodia, Lao, Vietnam, etc.) he came back with a sense that the Western art world cannot afford to ignore what's going on in so many countries. The future centres of the art world, he said, will be in the South. Places like Sao Paulo, Dubai, Singapore, Mumbai or Mexico will take over from New York. Going through his slides, which showed selected (and exciting) art pieces and art practices from the countries he visited, he built a strong case against the uninformed Western dismissal of the developments in those areas of the world. "Cambodia? There's nothing going on there." Not so. The narrow Western European and American horizon leaves all these up-and-coming future capitals for the arts out, and us out from them. That's exactly how Albertine De Galbert, a friend of Alexis's and also a French art critic, felt after visiting many Latin American countries and realising the strength of the art produced there and the lack of connection between practitioners from neighbouring countries. As a response, she started an online resource called artesur.org that does just that: connect the Latin American art world. Or as they put it "to guide art lovers and professionals into the multitude of artistic ways, techniques, events, and exhibition spaces of this region." Alexis's talk clearly resonated with the local art crowd that came to listen to him. Art fairs and biennials in Mumbai, Dubai or China feel closer and more relevant to them than the Western biennials. The challenge for them, though, may be how to develop a local language that counters the effects of economic globalization, always ready to flatten cultural differences and favour recognisable, copycat aesthetic approaches.

|

Robert Cervera Amblar

Sculpture, installation, writing. Archive:

July 2013

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed